Donating blood stem cells

A blood stem cell transplant can be lifesaving, but the donor has to have blood cells that are genetically very similar to the recipient (1). Often, the ideal donor is a close relative. But only around one in three patients have a relative who is a match (2). So donor registers have been set up around the world to find donors to provide blood stem cells for their treatment.

Donating your stem cells is a generous act. You do not get paid, although DKMS will reimburse you for costs related to your medical assessment and cell donation.

Eligibility to donate blood stem cells

To be a blood stem cell donor in the UK, you must:

- live in the UK

- have a body mass index (BMI) below 40 (3)

- be in good health (4).

You have to be between 17 and 55 years old to register. We will keep your details until your 61st birthday and you can donate stem cells up to that age. We will check regularly that you are still willing and able to donate.

There are a number of health conditions that mean you cannot donate, therefore, an early part of the recruitment process involves completing a detailed health questionnaire..

Swabbing

If you meet all the conditions, we will send you a testing kit in the post. This contains a swab that you put in your mouth and rub on the inside of your cheek. It is completely painless. The swab picks up some skin cells for genetic testing.

You post the swab back to DKMS, where it is tested. If the tests show that you could be a match for someone on the register, we will ask you for a blood sample (5).

If there is not currently a possible match we will keep your test results on the donor register in case we find a match in the future.

Matching a donor: HLA matching

We carry out a series of genetic tests on your cheek swabs, called HLA matching. HLA stands for ‘human leucocyte antigen’ (5). The better the match, the less likely it is that the patient’s immune system will reject the transplanted tissue or stem cells (8). You may hear this process called ‘tissue typing’. It is used for organ transplants as well as stem cell transplants.

HLA molecules are on the surface of most cells in the body (5). They help your immune system tell your own body tissues apart from anything ‘foreign’, such as viruses and bacteria.

The genes with the blueprint for these molecules vary from person to person. Researchers have now found more than 20,000 variations in HLA genes (7). Your particular set of HLA molecules and genes make up your personal tissue type (5).

At least 10 different HLA genes need to be tested (1). To be a donor, you need to have at least nine that are the same as the potential patient’s. The DKMS Life Science Lab currently tests 24 different HLA genes. As well as lessening the chance of rejection, a good match also means the patient is less likely to have complications after their stem cell transplant (9).

Keeping your donor profile up to date

The way labs test cell samples for a match is getting better all the time. Doctors and researchers continue to find out more and more about stem cell transplants and how to carry them out safely. They now screen for infections that could be a potential risk to the patient receiving the stem cells (10). They also know more about health conditions in the donor that could be a problem, either for them or for the potential patient (4).

If you gave your sample a few years ago, we may ask for a re-test. This will make sure the information we have on our donor register is as detailed and current as possible. We will send you another cheek swab testing kit and another health questionnaire. You complete these and send them back, exactly as you did before.

If you have a common combination of HLA markers, we may ask you to fill out the health questionnaire every two years. We will also ask you to confirm that you are still willing to donate. This ensures that if we find a match, we can get things going much more quickly.

If you are a match

Blood sample

If we think you may match a patient needing stem cells, the first thing we do is ask you for a blood sample. We use this for confirmatory tissue typing, to make sure you are the best possible match (5).

We will also check your blood sample for signs of infection, including HIV and hepatitis, as these could be dangerous for the patient receiving your stem cells (5).

Sometimes, we already have all the information we need on file and do not need a blood sample from you at this point (5).

Medical examination

The next step is your medical examination. We do this for every donor to make sure you do not have any health problems that could make donating stem cells a risk for you.

This health check takes place about two to four weeks before the donation. Our doctor will ask questions about your medical history and carry out a physical examination. We will also do some tests, including a heart test (ECG). We will also need another blood sample, which we will use to further test your health.

How donation works

There are two ways that doctors can access your blood stem cells:

- peripheral blood stem cell collection: taking them directly from your bloodstream

- bone marrow collection: taking from your bone marrow.

You may hear your doctor call stem cell or bone marrow collections a ‘harvest’.

Which type of collection you have will be decided by the specialist doctors treating the patient who will receive your stem cells. Around nine out of 10 blood stem cell collections are done directly from the bloodstream. There is information on both of these techniques below.

Only a small percentage of your blood stem cells are collected, so there will be plenty left for you!

Donating stem cells from your bloodstream

Before you donate stem cells, you need medication, G-CSF or Zarxio, to increase the number circulating in your bloodstream. You receive it as a small subcutaneous injection just under your skin once a day for up to five days (11). We will show you how to inject this yourself if you are happy to do that. Otherwise, you can go to your GP or have a nurse visit to give the injections.

G-CSF is a growth factor that encourages your bone marrow to make a lot of stem cells. These spill out into your blood circulation (11).

G-CSF can have some side effects. You may have flu-like symptoms, including aches and pains and headaches (12). The side effects are usually quite mild. A regular over-the-counter painkiller will help to control them.

G-CSF can also cause your spleen to become larger than normal (12): you are unlikely to notice this as it will not last long. Make sure you do not put added pressure on your spleen. You should not do any weight training, contact sports or hard physical work from the day you start G-CSF until six days after you have donated your stem cells.

Having G-CSF is very safe. We have monitored more than 80,000 donors having G-CSF over the past 20 years, there is no evidence of any lasting effects.

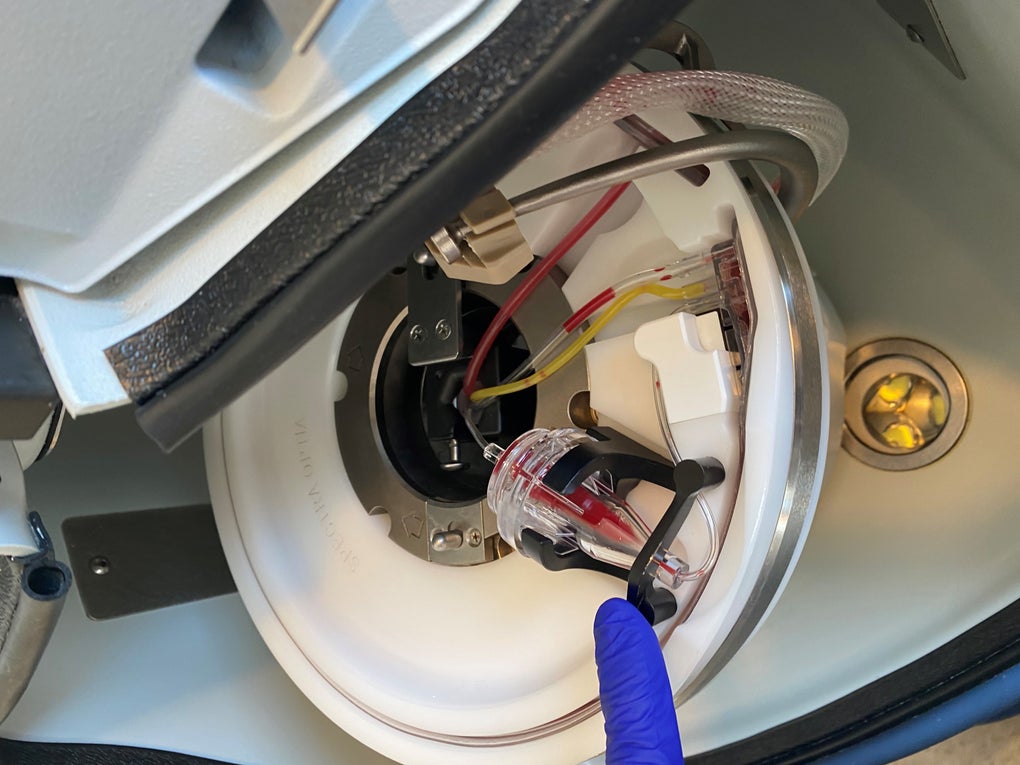

Having your stem cell collection

On the day of your collection, you come to the collection clinic. You have a drip put into each arm. Your blood flows out of one of the drips, through a machine (called a cell separator) and back into your body through the drip in the other arm. You do not need any sort of anaesthetic and will be awake throughout (13).

Sometimes the collection process lowers your body’s calcium levels (14). This is caused by a medicine you have to stop your blood clotting in the machine (15). Tell your nurse if you have any tingling around your mouth or get muscle cramps. You may need an intravenous top-up of calcium through your drip (14).

The collection takes between three and five hours. You can go home after it is finished.

A second collection

Very rarely do we need a second collection; usually one is enough. We may need a second collection because:

- the transplanted stem cells have not yet multiplied and developed successfully in the patient’s body

- the disease the patient is being treated for is coming back (a relapse)

- the patient’s body is rejecting the transplanted stem cells

- the patient needs a stem cell boost, to kick start their immune system

The second collection is usually smaller than the first. You usually have it done at the same collection centre where you had the first one. If needed, the second collection is likely to be within a few months of the patient having the transplant but could be up to two years later.

You do not have to do a second donation and we do not take it for granted. However, your second donation could be vital for the patient’s survival; we, and they, will be very grateful if you agree.

Donating blood stem cells from your bone marrow

To donate stem cells from your bone marrow, you will need to come into hospital for a couple of days. To have the marrow taken, you have a small operation under general anaesthetic. Once you are asleep, the doctor puts a needle into your hip bone (pelvis) and draws out some bone marrow into a syringe. To get enough bone marrow, the doctor will need to put the needle in several different places (16).

You will have about one litre - just under two pints - of bone marrow taken out. This seems like a lot, but it is only about five percent of your total bone marrow. Your body will make up the loss within a few weeks.

It is usual to stay in hospital for one or two nights after your donation. Your hips are likely to be a bit sore. Do ask for painkillers if you need them. When you go home, you will need to spend a few more days recovering.

Because this is an operation, however small, there are some potential risks. These are mostly related to the anaesthetic. You will have a thorough health check beforehand and a consultant anaesthetist will make sure everything is as safe as possible for you.

Recovering from donating blood stem cells

Donating stem cells often makes people feel very tired (14,16). How long it takes to recover from this depends partly on how you had the stem cells collected (17).

If you donated from your bloodstream, it takes around seven days on average to feel fully back to normal (17).

If you donated from your bone marrow, full recovery usually takes longer – up to three weeks. But you should be fit enough to get back to work and your other usual activities within two or three days. Your doctor may suggest that you take iron tablets for a few days if your red cell count is lower than normal (anaemia) (18).

Lymphocyte donation

Sometimes, the person who has received your stem cells will benefit from a further donation of lymphocytes. This is a type of white blood cell that is very important in immunity. If you are asked to donate these, it will most likely be between three and 12 months after the patient had the transplant.

There are two main reasons why your patient may need some of your lymphocytes (19, 20):

- they have a mix of yours and their bone marrow cells – but the proportion of donor bone marrow is not high enough. An infusion of your lymphocytes can kick-start their immune system which can increase the proportion of donor cells.

- there are signs that the disease they are being treated for is coming back (relapse). Your lymphocytes can help their immune system fight it off.

Donor lymphocytes can also help the patient to fight infections.

How you donate lymphocytes

You donate lymphocytes in the same way as you donate stem cells from your bloodstream, through a drip attached to a cell separator machine (21). This is usually at the same collection centre where you donated stem cells.

You do not need any growth factor injections beforehand, as there will already be lots of lymphocytes in your blood. The machine takes the lymphocytes out of your blood and you have the remaining white cells, red cells and plasma, the liquid part of blood, put back into your other arm. The process takes around two to three hours (18). This donation is lower in volume than for stem cells: about 200ml which is less than half a pint (21).

Sometimes, you will have lymphocytes taken at the same time that you donated stem cells. These will be frozen in case the patient needs them in the future (21); you won’t have to go through the collection process again.

Follow up

After you’ve donated stem cells, your blood counts may be below normal. This is nothing to worry about and your body makes up the loss within a few weeks at most (17) You will have a blood test after four weeks to make sure your blood counts have recovered.

At DKMS we take the welfare of our donors very seriously. To make sure there are no long-term effects, we monitor the health of our donors for 10 years. We will send you a health questionnaire six months after your donation and then every year for the next 10 years. If you do not want to carry on with these at any point, just let us know.

Contact with ‘your’ patient

Some people feel that they’d like to meet the patient who has received their stem cells. There are regulations that prevent this for two years after the donation. This is because the patient needs space to recover and because they may need a second donation at some point within this time. We are committed to protecting your privacy and that of the patient. We also do not want donors to feel pressured if the patient needs a further donation from you in the future.

You can only meet after two years if the patient asks to. But you can write an anonymous letter or email if you would like to, which we will pass it on to their treatment centre. There are some conditions on what you can include in the letter. Please see our page on writing to ‘your’ patient for more information.

We know that donors often worry about how ‘their’ patient is doing. We contact the treatment centre around three months after the transplant to find out how things are going. As soon as we hear (this can take a lot longer than three months for some countries) we will let you know.

Some donors do not want any updates, which is of course fine. Just let us know and we will not pass the information on. You can also change your mind at any time – again, just get in touch with us.

Some people like to write about being a donor on social media. Again, that’s fine. But please do bear in mind that you cannot post anything that would give away confidential information.

Social media and the media

We have produced guidelines on talking to the media or posting on social media. We’re also happy to talk this over with you. Just get in touch, telephone 020 8747 5660 or email followup@dkms.org.uk.

References

1. Furst D, Neuchel C, Tsamadou C et al. HLA matching in unrelated stem cell transplantation up to date. Introduction. Transfusion Medicine Hemotherapy, 46, pp326-36. Published October 2019.

2. Tiercy J-M. How to select the best available related or unrelated donor of hematopoietic stem cells? Introduction. Haematologica, 101(6), pp680-7. Published June 2016.

3. Donor Information. I’ve been found as a potential match – what happens next? Why is my height and weight so important? British Bone Marrow Registry (BBMR). Published September 2020.

4. Medical guidelines when you match a patient. Be The Match. Accessed July 2021.

5. Confirmatory typing. DKMS. Accessed July 2021.

6. HLA matching. National Cancer Institute. Accessed July 2021.

7. Furst D, Neuchel C, Tsamadou C et al. HLA matching in unrelated stem cell transplantation up to date. Methodical aspects of the investigation of HLA incompatibility studies. Transfusion Medicine Hemotherapy, 46, pp326-36. Published October 2019.

8. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Complications: graft failure. Medscape. Last updated June 2021.

9. Tiercy J-M. How to select the best available related or unrelated donor of hematopoietic stem cells? [Abstract]. Haematologica, 101(6), pp680-7. Published June 2016.

10. Donor selection for hemoatopoietic cell transplantation. Other considerations: CMV status. UpToDate. Last updated January 2021.

11. Filgrastim. Indications and dose: mobilisation of peripheral blood progenitor cells in normal donors for allogeneic infusion (specialist use only). NICE British National Formulary. Accessed July 2021.

12. Filgrastim. Side effects. NICE British National Formulary. Accessed July 2021.

13. Donating stem cells. Stem cells from blood. British Bone Marrow Registry. Accessed July 2021.

14. A transplant using your own stem cells. Collection of stem cells: from your bloodstream. Cancer Research UK. Last reviewed January 2019.

15. Donating stem cells and bone marrow. How stem cells are collected: collecting peripheral blood stem cells. American Cancer Society. Last updated August 2020.

16. A transplant using your own stem cells. Collection of stem cells: from your bone marrow. Cancer Research UK. Last reviewed January 2019.

17. After you donate. Recovery from bone marrow and PBSC donation. Be The Match. Accessed July 2021.

18. Donating stem cells and bone marrow. How stem cells are collected: Collecting bone marrow stem cells. American Cancer Society. Last updated August 2020.

19. Having a donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI). When is a DLI used? Anthony Nolan. Published March 2019.

20. Donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI). Collecting the donor lymphocytes. Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust. Published July 2019.