Blood cancer: Lymphoma

Understanding lymphoma

Lymphoma is one of the three main types of blood cancers, alongside leukaemia and myeloma.

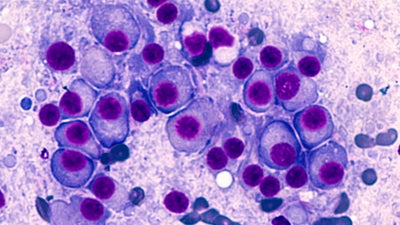

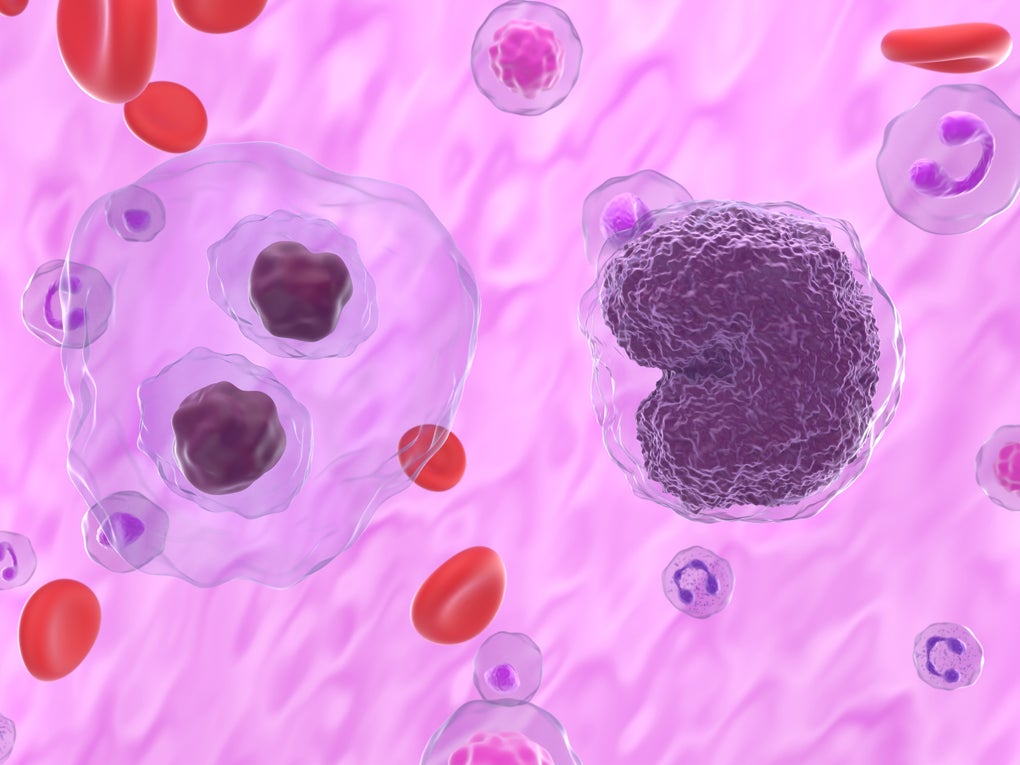

Lymphoma starts in your lymphatic system, which is a crucial part of your immune system. This disease primarily affects a type of white blood cell known as lymphocytes, which help your body fight infections. Lymphoma can develop in various parts of your lymphatic system, including your lymph nodes, spleen, bone marrow, and other organs. There are two main categories of lymphoma: Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

If you or someone close has been diagnosed with lymphoma, understanding the condition is essential. Recognising symptoms early, exploring treatment options, and providing emotional and practical support are key to managing the disease. Being well-informed empowers you to make educated decisions about treatment and care, significantly impacting your prognosis and quality of life.

Learn more: Blood cancer

Types of lymphoma

Hodgkin lymphoma: this type is relatively rare and is identified by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells. It often starts in lymph nodes in the upper body and spreads in a predictable manner. Hodgkin lymphoma has several subtypes, each with unique characteristics and treatment approaches.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma: this broader category includes numerous subtypes, which can be classified based on whether they originate from B cells or T cells. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas vary widely, from slow-growing (indolent) to fast-growing (aggressive) types.

Other rare types of lymphoma: These include cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which affects the skin, and primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma, which starts in the brain or spinal cord.

Risk factors & myths about causes

Several risk factors can increase your likelihood of developing lymphoma. These include:

- Genetics: a family history of lymphoma can slightly elevate your risk.

- Age: the risk of Hodgkin lymphoma peaks in early adulthood (ages 15-40 years) and late adulthood (after age 55). Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is more common in older adults (typically over 60).

- Gender: lymphoma is generally more prevalent in men than in women.

- Weakened immune system: conditions such as HIV/AIDS, autoimmune diseases, and immunosuppressive treatments (e.g., post-organ transplant medications) can increase your risk.

- Infections: viruses like the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV) and hepatitis C, as well as bacterial infections like Helicobacter pylori, are linked to higher lymphoma risk.

- Exposure to chemicals: certain pesticides, herbicides, and solvents have been associated with an increased risk of lymphoma.

There are several misconceptions about what causes lymphoma. For example, some believe that injuries can cause lymphoma, but there is no scientific evidence to support this. Additionally, lifestyle factors like diet and exercise, while important for overall health, are not direct causes of lymphoma.

Recognising lymphoma symptoms

The most common symptoms of lymphoma include:

- swollen, painless lymph nodes in your neck, armpits, or groin

- fever and night sweats

- unexplained weight loss

- fatigue and general weakness

- itchy skin

- pain in your chest, abdomen, or bones.

While symptoms for both types of lymphoma can overlap, there are some distinctions. Hodgkin lymphoma often presents with a triad of night sweats, fever, weight loss and additionally a swelling of the lymph nodes for over four weeks. It may also cause intermittent fevers or pain in the affected lymph nodes after alcohol consumption. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma can manifest with more diverse symptoms, depending on the specific subtype and can spread to other organs, causing additional symptoms like abdominal pain or fullness(because of spleen swelling) and respiratory issues.

Treatment options for lymphoma

Lymphoma treatment varies depending on the type and stage of your disease. Common strategies include:

- Chemotherapy: this is the cornerstone of lymphoma treatment, utilising potent drugs to destroy cancer cells. These drugs can be administered intravenously or orally and are often used in combination to enhance effectiveness.

- Radiation therapy: this method uses high-energy beams, like X-rays, to target and kill cancer cells in specific areas. It's typically used when lymphoma is localised.

- Immunotherapy: this innovative treatment boosts your immune system to combat cancer. It includes the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T cell therapy, and targeted antibodies such as rituximab and brentuximab vedotin.

- Targeted therapy: this approach involves drugs that specifically target cancer cell components, such as proteins or genes, to inhibit their growth and survival.

- Stem cell transplant: for cases where initial treatments fail, a stem cell transplant can restore healthy bone marrow by infusing new stem cells into your body.

Emerging treatments like chemoimmunotherapy, which combines chemotherapy and immunotherapy, are showing promise by leveraging the strengths of both approaches to improve outcomes and reduce side effects.

Learn more: Treatments for blood cancer and blood disorder

Outlook and living with lymphoma

Managing lymphoma focuses on controlling the disease, achieving remission, and enhancing your quality of life. Your prognosis varies based on the type of lymphoma (Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin), stage at diagnosis, age, overall health, and treatment response.

A healthy lifestyle and emotional support from family, friends or support groups are crucial. Each patient's treatment is tailored to their unique medical history and preferences, optimising effectiveness and minimising side effects.

Continuous advancements in research and ongoing clinical trials are steadily enhancing the understanding and treatment of myeloma. Staying informed, maintaining open communication with healthcare providers, and being proactive in managing your health can significantly improve outcomes and quality of life.

Learn more: Blood cancer research at DKMS

A blood cancer or a blood disorder diagnosis can feel overwhelming, but remember, you're not alone. Our team is here, ready to provide support and guidance. Partnering with DKMS can help you share your story and amplify our combined efforts to expand the stem cell registry. This increases the chances of finding a potentially lifesaving match for patients with blood cancers and blood disorders, if a stem cell transplant becomes necessary.

Your wellbeing is our priority, and we're committed to supporting you so do reach out to us. Together, we can create more hope and opportunities for people living with blood cancer.

References

1. Summary. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. BMJ Best Practice. Last reviewed September 2024.

2. What is lymphoma? Lymphoma Action. Last reviewed September 2024.

3. Lymphoma. Mayo Clinic. Last reviewed September 2024.

4. Lymphoma. Yale Medicine. Last reviewed September 2024.

5. Overview of Lymphomas. Merck Manuals. Last reviewed September 2024.

6. Pathophysiology and classification. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. BMJ Best Practice. Last reviewed September 2024.

7. Epidemiology. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. BMJ Best Practice. Last reviewed September 2024.

8. Who gets it? Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Lymphoma Action. Last reviewed September 2024.

9. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [Symptoms]. Lymphoma Action. Last reviewed September 2024.

10. CAR T-cell therapy. Cancer Research UK. Last reviewed September 2024.

11. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [Outlook]. Lymphoma Action. Last reviewed September 2024.

12. non-Hodgkin lymphoma survival [Diffuse large B cell lymphoma]. Cancer Research UK. Last reviewed September 2024.

13. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. NHS. Last reviewed September 2024.